Where should the Chinese prediction market explore?

The Unpredictability of Human Nature and the Chinese Community’s Western Aspirations

The concept of randomness has its roots in gambling, while geometry originated with ancient Greek philosophers—placing it at a natural disadvantage in terms of prestige.

Expressing and quantifying uncertainty is the foundational challenge of probability theory, and it’s precisely this that sets prediction markets apart from traditional gambling. PolyMarket’s documentation argues that casinos extract a house edge from every bet. Statistically, under the law of large numbers, every gambler eventually loses.

Prediction markets are true PVP, two-sided competitions. Polymarket doesn’t charge for deposits or withdrawals, nor does it take fees from trades, completely eliminating platform interference with randomness.

Yet that alone isn’t enough. PVP does not guarantee Market Price equals Probability—you also need expectation. Only when expected returns are quantifiable and cover the cost of speculation can prediction markets break free from the constraints of gambling and become genuine financial instruments.

Entertainment-Driven Odds

All forms of authority—political or journalistic—are ultimately just digital wins and losses.

Information monopolies don’t depend on hiding sources; they rely on controlling distribution channels.

Modern journalism took shape under World War II censorship. Wilbur Schramm established communications as an independent field, blending sociology and statistics with qualitative and quantitative methodologies, turning journalistic professionalism into an industry shield.

As the voting population expanded (including women, Black Americans, and youth), polling began to directly influence politicians’ futures. Inferring collective voter tendencies from small samples became a lucrative, commercial pursuit for media, political parties, and even opponents.

Yet both polling and news have long been B2B businesses: media sell audience attention to corporations. The public is just a commodity, unable to profit from their collective awareness or preferences—mirroring the frustration with centralized platforms.

Privacy infringement is only a surface issue; the real problem is that platforms don’t pay users.

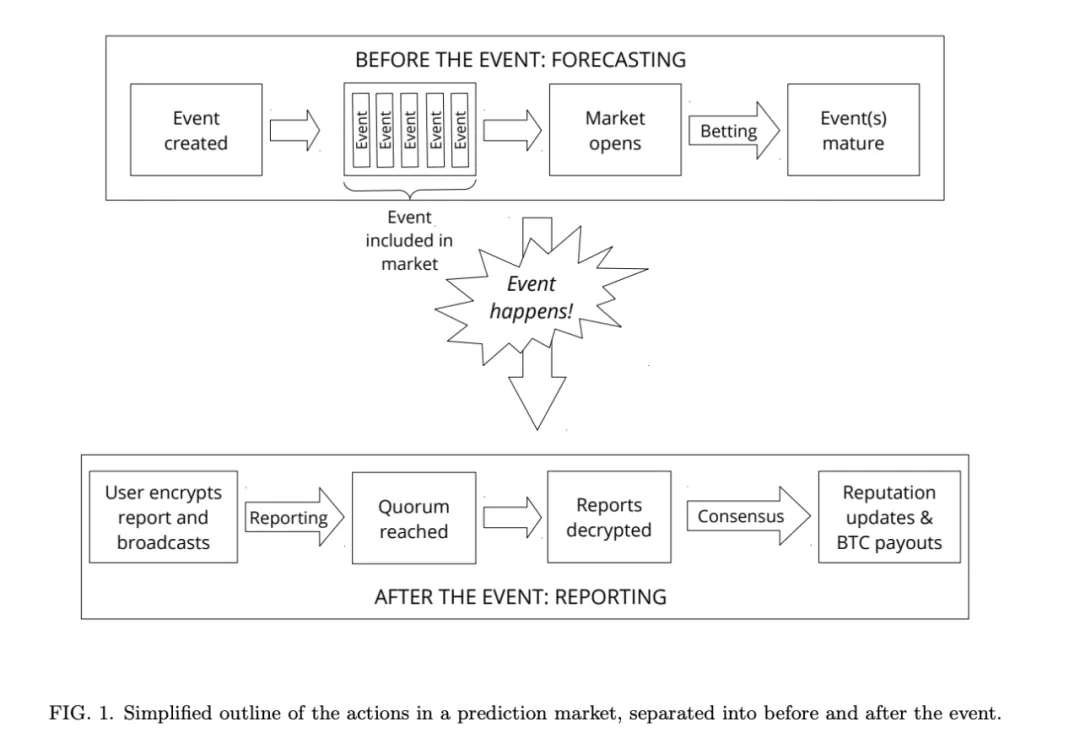

As early as 2014, academics were exploring how blockchain and prediction markets could disrupt the traditional centralized “house” model. Vitalik recalls the result of this thinking was the inception of Augur v1 in 2015.

But Augur v1 was built on Bitcoin sidechains, and Ethereum was not yet ready for large-scale on-chain applications. Augur’s relentless pursuit of decentralization kept it niche, unable to generate positive externalities, eventually fading into the crowd.

Image: Augur v1 architecture

Image credit: @AugurProject

By DeFi Summer 2020, with DEXs and lending platforms thriving, trailblazers like Hyperliquid’s Jeff and Polymarket’s Shayne Coplan were developing next-generation prediction markets, leveraging Ethereum, L2s, and centralized governance. Technology had solved efficiency issues; lack of consumer demand was now the main bottleneck.

Sometimes, timing is everything.

- • The global lockdowns of 2020 made online lifestyles mainstream everywhere, including prediction markets;

- • The 2022 World Cup triggered a peak in global gambling activity, with $100 billion in online betting—much of it driven by the tournament;

- • The 2024 presidential election saw Trump’s unpredictable antics drive unprecedented global engagement. Even a sliver of this traffic is a windfall for Polymarket.

After the election, Polymarket maintained its market share through steady fundraising, generous fee waivers, and aggressive moves into sports—just as Hyperliquid did post-token launch. Polymarket has weathered its riskiest period.

The 2026 World Cup will be the make-or-break moment for Polymarket’s emergence as an online prediction market giant. Political uncertainty is too high; sports events offer safer, more reliable returns.

Image: Prediction ≠ Gambling

Image credit: @zuoyeweb3

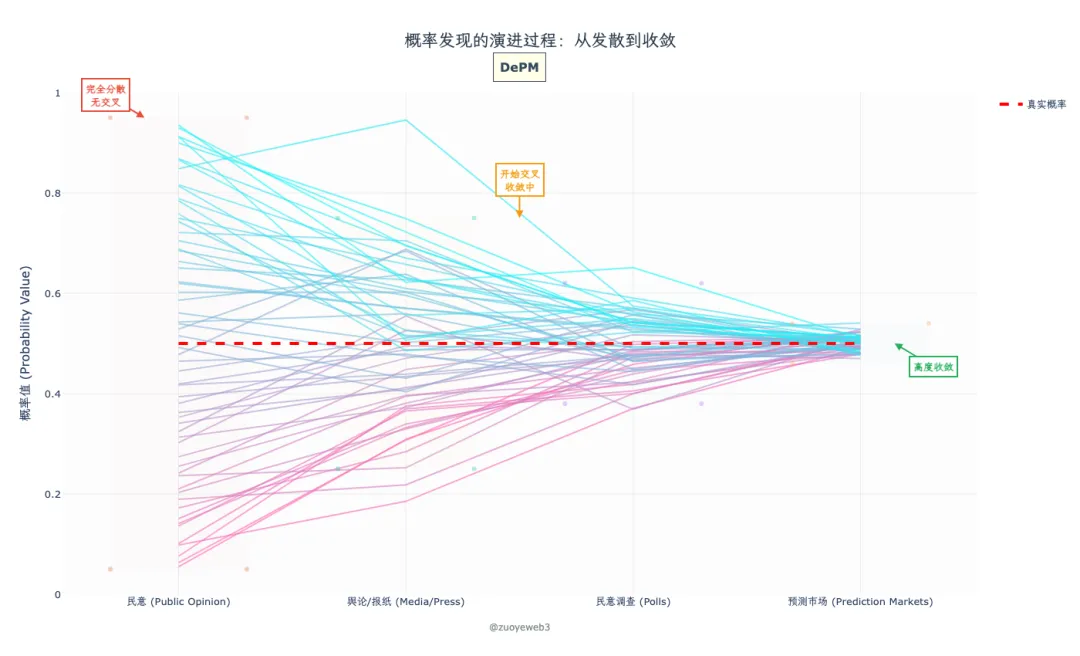

What makes prediction markets so efficient? Take Trump’s campaign: 240 million eligible U.S. voters form the total sample, but only 150–160 million actually vote (the effective sample). Beyond reliably red or blue states, a handful of swing states—and even swing counties—determine the outcome.

Polls targeting swing states are thus critical. Mainstream pollsters like Gallup design scientific sampling methods because polling every voter is impossible. Inferring the whole from small samples is a massive challenge.

The paradox: a key minority can always influence the majority. Prediction markets enable ongoing analysis of sample parameters and allow participants to bet on higher probabilities before actual outcomes are known.

So, prediction markets aren’t better at sampling—they’re better at constantly recalibrating the sampled parameters, with every opinion reflected instantly in odds.

Polymarket is essentially a “clustering algorithm,” continually sampling discrete data for the highest probability and cross-validating it against the final results to improve accuracy.

Odds represent pricing for bullish/bearish, disagreement/consensus positions. In Polymarket, the basic unit is the Event, and each standard contract is minted as 1 USDC, with Yes + No = 1. For example, Yes at 0.5 must be matched by No at 0.5.

Suppose Alice and Bob buy at 0.1 Yes and 0.1 No, and the market price is 0.5:

- • If Alice expects the probability to exceed 0.5 and is proven right, she nets 0.9 USDC;

- • If Bob expects it won’t exceed 0.5 and sells, he locks in 0.5 USDC, netting 0.4 USDC.

Initial price discovery and volatility require market makers and Polymarket’s market creation permissions. The platform uses a CLOB model similar to Perp DEXs, supporting advanced order types like limit orders.

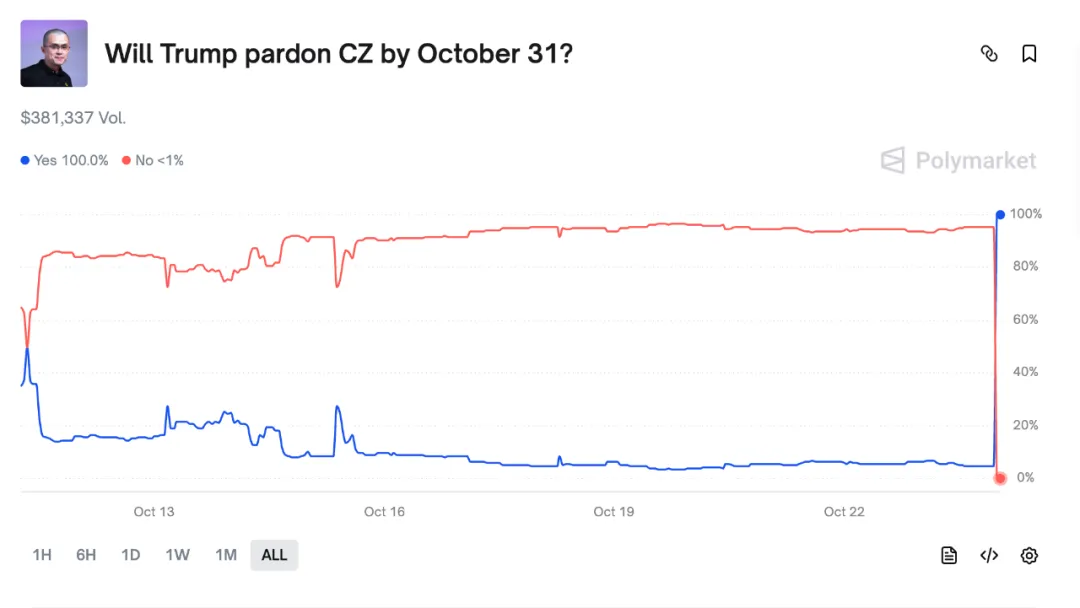

The mechanism is straightforward: Yes + No always equals 1; the difference between the current price and 1 is the profit margin. For example, a 93% probability means 0.93 Yes + 0.07 No = 1 USDC. If the outcome flips to No, that 0.93 is the surprise profit.

Image: Upset moments

Image credit: @Polymarket

Bets can be bought or sold at any time, providing liquidity—a far more efficient market-making method than fixed bets. Yes/No positions are each other’s profit/loss source, making this a pure PvP market where the platform simply ensures fair matching.

This article does not cover details such as oracles, governance, market openings/closings, or dispute resolution. In essence, Polymarket is a commercial internet prediction product using blockchain and stablecoins—decentralization is largely beside the point.

Entertainment Is About People, Not Events

The expansion of monopolies is often driven by collusion between organized capital and organized labor.

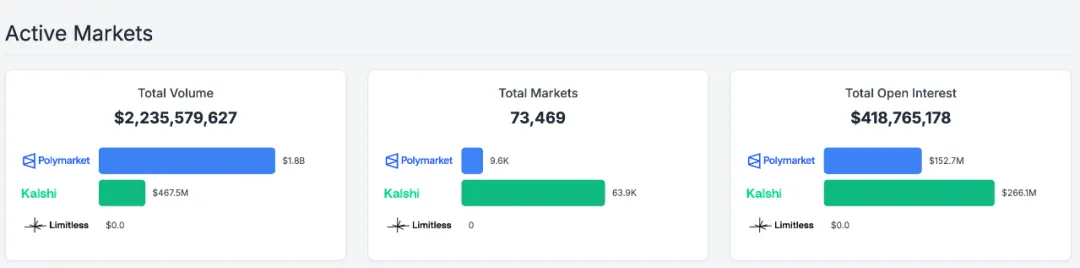

Polymarket’s three pillars are U.S. politics, news events, and sports. Its chief competitor, Kalshi, is compliance-focused and partners with Robinhood, Jupiter, and others—trading profit for user growth.

Image: Data comparison

Image credit: @poly_data

Most new prediction markets aspire to be Blur’s equivalent to OpenSea, attracting retail users with potential airdrops and launching tokens. Few directly challenge Polymarket or Kalshi.

Compliance isn’t the main driver—Polymarket’s compliance is a pricing issue, while Hyperliquid’s is much more significant. Their liquidity is on completely different scales.

Ultimately, U.S. elections are a niche market, while sports appeal globally. Polymarket reflects young Americans’ preferences; atomized users may avoid betting platforms or only watch esports, but many still bet on sports.

Before Polymarket, Kalshi, and NFL partnerships, NBA teamed up with DraftKings and FanDuel in 2023. NYSE’s parent invested in Polymarket, and FanDuel joined forces with CME—institutional capital is moving in.

NBA match-fixing enforcement has become less significant since the Supreme Court legalized sports betting in 2018. It won’t halt PL or Kalshi, though the future and scale of sports betting remain uncertain.

Similar to China’s Moutai challenge, virtualization and atomization among youth are irreversible. Events are seen as old people’s games; beyond pro- or anti-Trump, many simply don’t care.

From defending Shanghai in cyberspace to U.S. Marines quoting “Helldivers 2” lyrics, shared online spaces often connect people who never meet offline.

Beyond generational attitudes, gambling and illicit activities are minor issues for prediction markets. With Polymarket at $1.5 billion and Kalshi at $1.2 billion valuations, both have reached their peak.

Organized capital sticks to predictable political, news, and sports events. The future lies in what else can capture young people’s attention and investment in cyberspace.

Globally, only entertainment personalities—rather than events—can unite young audiences and capture both their attention and spending.

Not only do young people care about entertainment personalities, but Taylor Swift’s “pre-wedding split” could generate higher engagement than Trump if cross-platform marketing connected Xiaohongshu and Instagram.

During a celebrity’s peak, drama like fan feuds and “unfollow backlashes” is routine, much like Disney merchandise. Celebrities can be the foundation for secondary markets.

This is not hypothetical—financial participation in entertainment is a global trend.

Movie blockbusters sell T-shirts, MrBeast launches MrBeast Finance, G.E.M. invests in AI startups, and Kanye sells memes.

This is safer than NFTs or market manipulation. People bet on personalities; even insider info is absorbed into the market—fans care only about their emotional investment.

K-pop fan battles are the norm. Winning is everything—financial outcomes are secondary. Prediction markets could become the financial expression of fandom.

You could even create sophisticated hedging strategies—betting “No” on a movie before release hedges against associated reputation risk. Whether a film is quality or profitable is often clear during production.

Finance isn’t becoming entertainment; it is already highly entertainment-driven. In a fragmented world, some cheer prediction market licensing, some debate gambling definitions, others seek new opportunities.

The Trump family has invested in Polymarket; outsiders are still debating. Participating in these markets is the practical approach to generating returns.

Conclusion

The end of globalization is reflected in the decoupling of goods and services. We’re now entering a new era of service trade, but humans are drawn to collective excitement. Simply localizing U.S. elections for Thailand is pointless; it only shrinks the market.

Seeking consensus in a fractured world can create unique value, especially for Chinese entrepreneurs. Politics and sports are risky; underground operations reach a ceiling. The entertainment industry is the safest entry point.

CZ may face Western scrutiny for his Chinese identity, but predicting Kim Kardashian’s hip size is hardly a national security risk.

Statement:

- This article is reproduced from [Zuoye web3], with copyright belonging to the original author [Zuoye web3]. For any objections regarding reproduction, contact the Gate Learn team for prompt resolution.

- Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is referenced, translated articles may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?